Mahokenshi PC Review

I cannot tell if it is due to seeing all the trailers and demos on DarkZero and that is manipulating my view about card games and deckbuilding, but they seem to be everywhere nowadays. It seems every couple of weeks a new one is announced or released and gets added to the massive catalogue of options that fans of the genre now have. I can only assume it is down to the indie developer presence in the genre, which is adding to this wave of popularity. I personally have not played many deckbuilders. I like the idea, but I often pick and choose between the many available to get my card fix. Mahokenshi, developed by Game Source Studio and published by Iceberg Interactive, happens to be the first one I have come across in 2023, however, this is not only a deckbuilder but one that mashes it with something I rather appreciate: Japanese mythology.

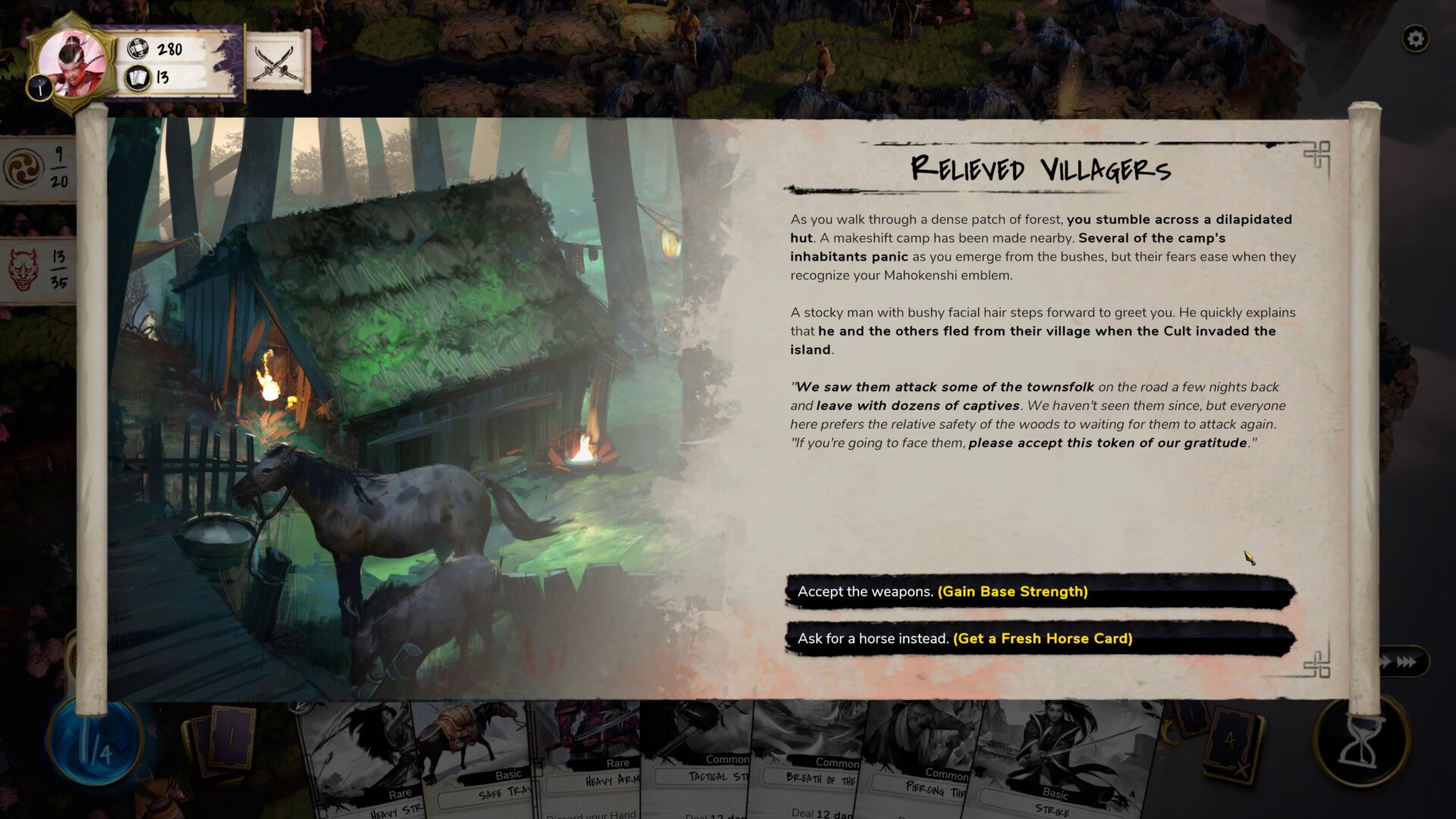

The general premise is to pick one of the four mahokenshi samurais that lead each of the four specific samurai houses: Sapphire, Topaz, Ruby, and Jade. These are powered by folklore creatures, such as the Tengu or Kitsune, which gives the four leaders their elemental themes and gameplay styles. There is a sort of story here, in that you are a mahokenshi on a mission to protect the floating celestial islands from enemy invasion, be it Onis, goblins, mages, and whatever other nasties are trying to take over this spiritual place, as this once holy land was clean of such beasts. It is a simple setup, but during the campaign, there are scenarios within the levels that offer player decisions which feel ripped right out of a pen-and-paper book, those choose-your-own adventures that tell the reader to go to a certain page depending on their choice. In this game, those pages are rewards with some sort of beneficial buff towards the player. Mahokenshi could have been without them, but this touch helps provide the game with a clearer presentation of its theme that is spread across all its visuals, art and sounds.

On the surface level, Mahokenshi is not just a deckbuilder, but more akin to a turn-based strategy game. Each mission features a unique map filled with hex-grids across varied terrain and a multitude of enemies set on top, as the player attempts to complete the mission objectives in one vs many situations. The landscape is important in Mahokenshi as there are advantages and disadvantages based on the type of terrain. Typically, moving cost one energy (the start of a mission has the player with a base start of 4), but going up hills or mountains might cost two or three, but these then in turn either offer defence or attack buffs that add to the base values for that turn. Of course, this means the enemies can do the same and will make the most of this in battle. Enemies will detect your hero if close by, so can be lured away from safety points and trapped in choke points across bridges, which is an advantage used in one mission where the player has to take down four tough Oni bosses who are coming towards a key structure. It is rare that the environment makes such an impact in a deckbuilder, but in Mahokenshi, it is almost as important as the deck in your hand when it comes to the strategies available, as the game will make sure you have to take advantage of this in the later missions.

Energy is the controlling factor that limits the player’s turn. Along with energy used to move, each card will also have an energy drain amount, mostly one, but stronger cards can require two or three, while elements that buff or incorporate discarding a card to play are usually rated zero energy cost. Expect familiar card gameplay mechanics to be here, as they deal damage, provide defence, buffs/debuffs, damage over time or help traverse ground for cheaper energy cost, which I found to be one of the most helpful cards in the game.

One element to make clear about Mahokenshi is this is not a roguelike, even if in the beginning the three of four characters are locked, only becoming available after completing certain missions in the campaign. The heroes do not have their own campaign, rather, they are available to be used to bring different playstyles into the campaign. I felt this was a strange idea, because each character starts at level one when they unlock, and you level them up by playing with them, but this means taking a lower level mahokenshi into the campaign after spending a few missions with others and getting the hang of them. The game gives small tips on how to play these characters on first use, so I see no reason to have them locked away like this. At least they often level up after a mission, so it does not take long to get them on equal grounds with other heroes.

Each time a character levels up they unlock more cards and gear. Each hero is focused on a playstyle. Ayaka focuses on sacrificing health for offence and can fly to reduce movement penalties. Kaito is the reverse, in that they favour defence and can cover themselves in thorns to damage enemies in their attack phase. Sota is a poison and mobility master, while lastly, Misaki, has skills in summoning support, casting area-of-effect spells and confusing enemies. Along with this, there is also a passive skill tree that is split into three sections. The skills here are permanent and are unlocked from the skill points gained for finishing objectives and side objectives within these missions.

A striking gameplay element that I found myself enjoying, and one that splits Mahokenshi from other major card games, is that the deck is cleaned out at the beginning of each mission. This is down to the game’s deckbuilding done during the current mission. At the start, the deck is a basic hand with a small number of cards. On the board are spaces that offer cards to select from that then become part of that deck for the remainder of the match. Towns and castles offer similar features, such as upgrading cards, destroying cards or purchasing new cards in exchange for money, which is found in chests or from defeating enemies. This adds an element of bespoke customisation based on what is happening during the mission. Since missions can have a variety of objectives; defending, attacking, sealing portals, taking down giant beasts which are charged up by support characters, surviving a number of turns, finishing in a number of turns, and many others, each one requires its own approach to overcoming the challenge.

An excellent example of level deckbuilding is a mission where the player is chased by four Onis and must retreat to a castle for help. I wanted to gain distance away from the Oni as much as possible, so I was selecting cards that would let me move one additional hex for free or at least move me more than one space for the same energy cost. Once hitting the castle, the leader wants you to defend, so then I began to rework my deck to be more offensive before the Onis arrived, which led to cutting them off across the bridges and damaging them with my new damage cards from the store. On the surface, it seems like a small change to some game mechanics, but in the terms of Mahokenshi’s campaign, this way gives the game a sense of building to requirement rather than just taking the best deck at hand for each run-through, which happens in roguelike deckbuilders. There is a decent amount of card types which are designed with distinct rules in mind that enable this bespoke approach to strategies.

Mahokenshi still suffers from deckbuilding randomness, something that seems a trait of the genre. The random generation of the deck order and the discard and recycle process back into the live deck can leave situations that either favour or handicap your turn. Sometimes you might have a brilliant draw and can slaughter an enemy that has high defence and health, but then on the other hand, the scenario where there is only one attack card in hand and must either try and work with what you’ve got. Maybe it is a movement card that adds defence so that you can take more damage, or in the worst case, there is no option other than to move or skip a turn and deal with the outcome of that unlucky scenario and have the flow of the mission interrupted until a good hand returns. If this is happening often, then there is the option to destroy cards in a deck by visiting one of the shrines, which limits the chance of a bad hand coming out with a reduced card count.

Some missions seem to prefer a certain hero’s playstyle, but that might be down to me being better at using a defensive character rather than a poison-based one. Mahokenshi gives off a false sense of difficulty in the beginning, as it must have been a few missions in until I got my first defeat. After that, the game turned up the challenge and I had to reevaluate my strategies as I was learning from my failed missions and adapting that into my follow-up attempts. Some players might want to stick with a singular hero, but there are reasons to level them up, as not only do they gain cards that share across each hero, and some that are unique to them as well, but items, which can be used after cooldown, can help buff the hero when called upon. This might require replaying some missions or levelling them up, or dying a few times, as experience still carries over even if the mission is a failure.

Each mission has side challenges that reward skill points. This gives reasons to perfect a mission while gaining experience and skill tree progression in the meantime to reduce some of the repetitive grind needed to level up all the heroes. The single campaign could also be seen as a negative, as people are used to the repeatability of popular card games that having one campaign that is around 17 hours might feel short without that replay value, but for me, personally, Mahokenshi was rewarding enough that I was happy to move on after it was done.

Presentation is an area that Mahokenshi does wonderfully for 95% of it. The Japanese theme is spread throughout all its art, from the great-looking environment stripped straight from a tabletop board game to the brilliant artwork for its short scenario backgrounds and amazing card artwork. One thing that it falters on is sometimes the details of card actions can overlay each other on the screen, which gives off an unpolished feeling. The only things that come across as basic in Mahokenshi’s visuals are the 3D models of the hero and the enemies, as you can zoom in and see they do not hold much detail. Not that you need to do that anyway, as this is a game that should be kept zoomed out to see the scale of the battlefield and the placement of enemies. The music is fitting for Japanese mythology, but I never found it memorable, I cannot even think of a piece of music to hum to as I write this part of the review, which shows how forgettable it is.

Mahokenshi is a visually eye-catching and mechanically solid entry into the big world of deckbuilder games and brings in a mixture of elements that will appeal to not just card/deckbuilder fans, but people who also enjoy board games. Mahokenshi blends tabletop gameplay with a more traditional campaign and progression system that rewards players with smart card plays, rather than being a card-based roguelike, which seems to be the trendiest take on the genre now. Mahokenshi’s hex-grid map and in-mission deck building allow it to offer a bespoke way of creating and adapting a deck based on the mission objective. This leads to missions that can change objectives on the fly and not have the player then suffer due to a badly built deck, as the player can adapt and alter strategies or card synergies by gaining more cards. It still suffers from some of the randomnesses that games built around card mechanics have, and I still do not like how it locks out three of the heroes at the start, which I can see causing people to ignore them rather than experiment after spending a short time investing in the first character. Clear that mindset, as I found that in the long run, this does not hurt the overall fun I had with Mahokenshi and its wonderful Japanese mythological presentation.