The Changing Cost of Gaming

Home video game systems first hit the markets in the early 70s, with the release of the Magnavox Odyssey in 1972. Developed from Ralph Baer’s prototypical “Brown Box” machine, the Odyssey represented a sea-change in technology entertainment. No longer was television a passive entertainment, but it could now be interacted with and involve players.

In the years since the Odyssey’s release, the gaming industry has weathered major crashes and innumerable controversies to become the $100bn powerhouse it is today, but how has the way we buy games changed in this time?

Consoles have become much cheaper

1977’s Atari 2600 was the first game console which really hinted at what games consoles would become. Released in 1977, it boasted a huge number of different games, loads of new innovations and, best of all, allowed independent developers to create their own games. However, this innovation came at a hefty cost, with the 2600 costing £117 at launch, or the equivalent of £504 in today’s money. In contrast, the Xbox One cost just £429 at launch, dropping to £300 about a year later.

Of course, some of the price gap between the generations comes down to advances in manufacturing and the price of technology coming down over the years, but a huge part of it is also down to economics. The demand for consoles and games today far outstrips anything at the time of the 2600, even during the “gaming boom” of the early 1980s. Over the course of 15 years, the 2600 sold 30 million units, whereas the Xbox One has sold 14 million in under 20 months.

With demand and sales this high, modern consoles can afford to be cheaper and still turn a profit, and this is true across the gaming industry, as it has expanded from $6bn in 2002 to $24bn in 2013.

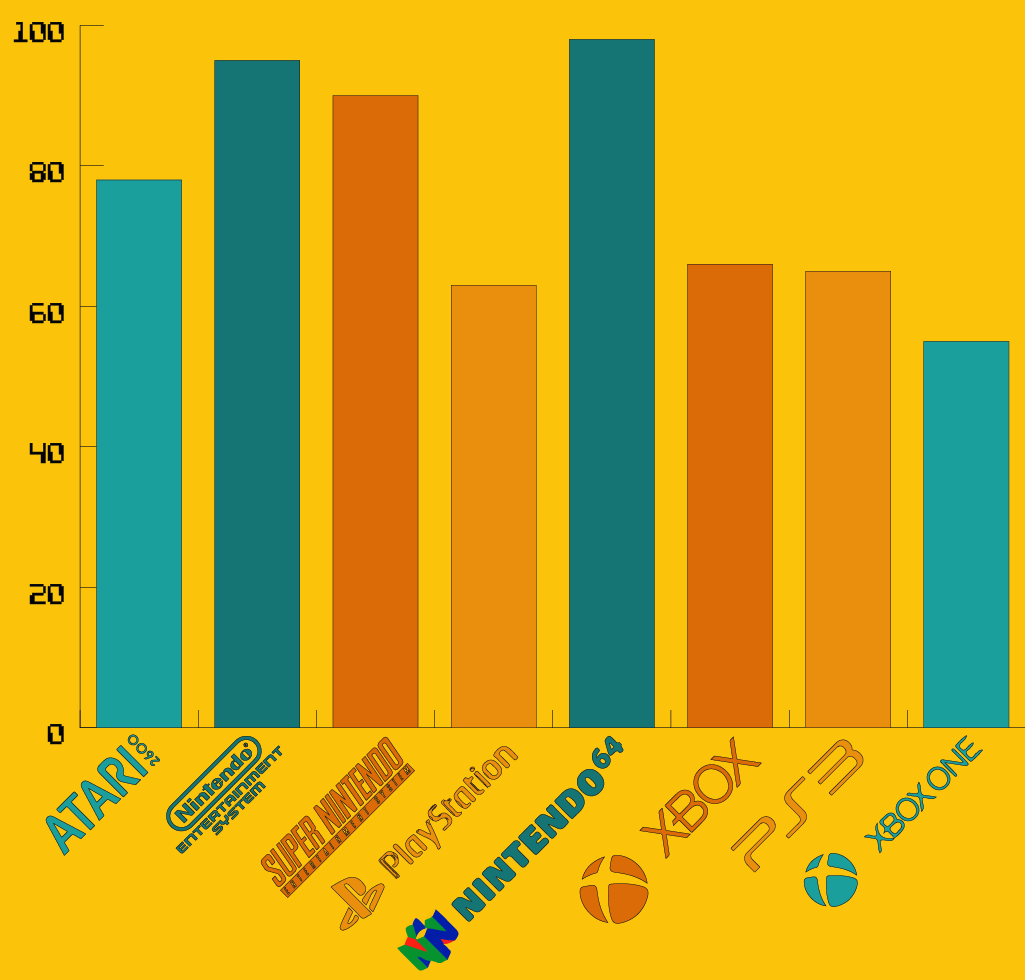

Games have also become cheaper

As the capabilities of consoles became more advanced, so too did the games themselves. Over the 80s and 90s the price of game cartridges rocketed, as consoles became cheaper. For example, the average NES title cost the equivalent of £62 today, and SNES titles cost around £60. The PlayStation was the first console to buck this trend when it launched in 1994. Whilst the PlayStation console itself was more than £100 more expensive than its main competitor, the Nintendo 64, the games were significantly cheaper, costing on average the equivalent of £40 compared to the average N64 game costing £64.

Average price of games, adjusted for inflation | source

Some of this pricing discrepancy is down to Sony’s adoption of discs as opposed to the pricier cartridges Nintendo used. However it was also a strategic decision of behalf of Sony which paid off, with PlayStation selling 102 million consoles, more than three times more than Nintendo did. This payment model has stuck, and for the past two decades, game prices have been significantly cheaper than they were in the late 80s and early 90s.

However, the biggest change in the way we buy videogames has been happening over the last couple of years, and it’s all down to smartphones.

How mobile gaming changed the way we pay to play

Over half of all smartphone users regularly use their phones for gaming, which means that mobile gaming is arguably bigger than console gaming. However, almost everything about mobile gaming is a departure from console gaming. Whereas console gamers expect increasingly sophisticated graphics and gameplay, with complex narratives and challenging themes, mobile gamers demand more repetitive, addictive gameplay, centred on short term rewards.

The problem being that the traditional payment model of a single payment for a game doesn’t work as well for mobile games like Candy Crush. This made mobile games difficult to monetise at first, but the “freemium” model gave developers a great way to make money from their games, and gave players a good way to enjoy the game at a fair price.

In theory, freemium works by allowing players to download a game at no cost and then make optional payments for added extras such as more lives or better armour. Currently over a third of the top grossing apps use the freemium model, and top earners such as Clash of Clans earn well over £300 million a year, netting more than the latest Call of Duty title.

Is freemium destroying mobile gaming?

By 1980, the video game industry was booming. Millions of television sets across America had Atari 2600s plugged into them and the market was absolutely flooded with competing consoles and game titles, many of which made by indie developers. The problem, however, was that many of these consoles and titles were of a sub-par standard. By 1983, the bubble had burst and the gaming industry completely crashed.

Many experts are starting to worry that we might be on the cusp of a similar crash in the mobile game industry, as the warning signs are all here. Not only has market growth in the mobile sector dwindled to half of what it was the year before but, just like in 1983, the marketplace is getting flooded with games of questionable quality. The iPhone Appstore is perhaps the best example of this, but even dedicated gaming marketplaces like Steam are being accused of loosening their quality controls.

The average user ratings of the top grossing mobile games of 2014 demonstrates players’ attitudes towards mobile games: whereas the top grossing console games had an average rating of 6.3 out of 10, the top 5 mobile games had an average of just 3.4.

Perhaps some of the disillusionment is down to how freemium games inherently work. Freemium depends on somehow incentivising players to make in-app purchases, and often lazy developers will do this through “road blocking” the game in order to force players to cough up. Whether this is done by inserting insurmountable obstacles or by imposing time limits, many popular freemium games squeeze money out of players through frustrating tactics, which is leading to something of a backlash amongst mobile gamers.

Whether or not mobile gaming is heading towards a crash, it is interesting to see how the freemium model that it spawned has affected the wider games industry. Everything ranging from MMORPGs to console FPS’s now include in-game extras for players to buy. For now, however, the traditional model of creating and selling games for a one-off sum is still far more profitable for bigger development companies, with the average blockbusting game earning far more than leading freemium titles.

Editor’s note: As a result of his research Geoff created micro-site videogameshistory.com which features fascinating infographics. See how past console financials compare and the top freemium and blockbuster retail titles go head-to-head. A real gem, check it out!